The Key Role of the Celebratory Communal Spaces of New York City

in Fostering Civic Consciousness, Social Justice and Proactive Environmentalism

An Adequate Response to the Threat to their Destruction

New York City is home to an impressive assemblage of buildings which serve its diverse religious

communities. Many are supreme examples of religious architecture. All house artifacts of great artisitic value.

There are approximately eight hundred and seventy three Christian churches of all denominations alone in

Brooklyn alone. Of these one hundred and fifty six churches serve the Catholic, one hundred and forty two

are Baptist, forty two are Pentecostal and twenty eight are Methodist. And the remaining five hundred and

five beyond to other Christian denominations. The religious establishment of the Jewish, Islamic, Hindu and

Buddhist religions surely raise the number of religious sites in Brooklyn much higher still.

Most importantly, the number of such facilities in New York constitute the axis of the community

spaces of the city. Indeed these facilities also represent a crucial part of the architectural patrimony of the city.

As such all deserve to be conserved and enhanced in order to better serve both the cultural and social needs of

the citizenry if not for their original religious purpose to continue to serve those most in need of whatever

faith.

It is increasingly evident that the drop in attendance of religious events in New York City is having a

grievous effect on the preservation of the architectural matrimony of the city. Dropping attendance has

combined with increasing maintenance costs to create a perfect storm which threatens the survival of the built

patrimony of all religious communities of New York City. This has presented the voracious interests of real

estate developers with the opportunity to demolish the architectural patrimony of the religious communities of

New York merely in order to erect buildings designed in fact for speculation and not much, if anything, else.

A recent article in the Gothamist reveals that the Catholic Church plans to sell one its churches in East

Harlem.(1) And this is merely one instance of a much broader problem faced not only by the Catholic Church

and all other Christian denominations as well as all other faiths. Indeed what is most important here is that the loss of these religious sites also threatens to inflict an

irreparable blow to the infrastructure of all communal centers of the city. And what is worse, the liquidation of

the religious architectural matrimony of the city in name of replacing it with so called “moderate income”

housing is merely a sham covering up a myopic scam promoted by the Real Estate industry. What is most

important to note is few if any of the religious communal structures which have been destroyed so far have

resulted in the construction of new moderate income housing. All have been replaced instead by purely

speculative real estate ventures which remain empty long after the completion of construction, resulting in a

worsening of the housing crisis instead of alleviating it. Of course the objective of Real Estate investors is

merely to secure tax right offs. Most importantly the destruction of the patrimony of religious buildings of the city would result in a

devastating blow to the social fabric of New York City as a whole. Thus immediate steps must and can be

undertaken to address a major thread to a key components of the architectural legacy of Brooklyn as well as

greater New York City which has always been a crucial underpinning of its social structure.

Ironically this scenario also underscores the intrinsic ability of the architectural legacy of cities to

serve as vehicles of contestation on the ills of their societies. Here they illustrate how this threat can be

addressed with relatively changes to the Zoning Laws with great potential impact on New York City.

Great good can be achieved by expanding the scope and of existing Air Rights of the buildings of

religious and other other communal groups by permitting their sale and transfer every give years for example.

This will create a secure recurrent income revenue for the protection of both the physical fabric of these

buildings as well as the communities they serve. And of course this would also protect the historic patrimony

of New York City.

Equally important these Air Rights should transferred of these out of the immediate zone or district of

these buildings to designated construction sites capable of accommodating higher densities of construction.

Such a strategy would preferably also channel the need for new and more housing with increased protection

against emerging environmental threats. In New York City this should be devised to direct the ability to build

to higher densities or heights to the coastal peripheries of the city subject to inundation from sea level rise.

This would also enable capturing the unique esthetic condition of coastal areas of the East and Hudson Rivers

while protecting low land zones. The lowlands of the south coasts of Manhattan would surely benefit from

erecting a coastal wall to secure all from sea level rise. And the same can be said of much of the opposite

shores of Brooklyn.

An excellent example of this would be to direct the transfer and assembly of Air Rights from

throughout Brooklyn to its waterfront on the East River and outer bay. Indeed, this East River waterfront is

fully capable of accommodating a host of super tall skyscrapers. This would also harvest the latent aesthetic

potential unique to the dimensional scale of both sides of the East River for New York City as a whole. Such a

policy would have the added benefit of combining the preservation of historic structures and environments

with designs confronting climate change. Indeed the construction of such megastructures along low lying

coastal areas would also have the benefit of effectively creating dykes protecting the quarters inland from

flooding. And of course, the construction of Supertall Skyscrapers would also serve as a virtual Viagra

capable of satisfying -well, only just perhaps- the voracious desire of all would be developers to “rise” ever

higher in their futile efforts to their reach their “gods”.

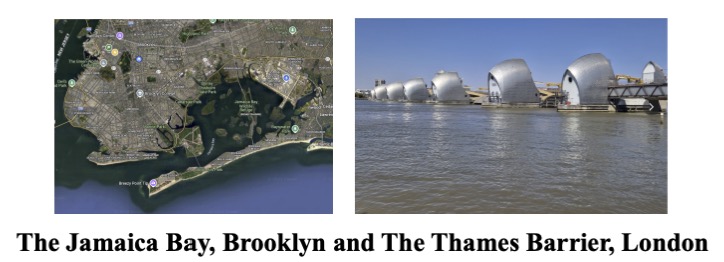

The transfer of these air rights to the maritime peripheries of the city underscores the complementary

ties between the preservation of historic structures and the design of new construction to address the

protection of the greater environments from the effects of climate change. Thus directing the use of air rights

to structures along the coasts of the city would give impetus to the protection of to structures protecting all

low lying neighborhoods from sea level rise. The neighborhoods about would benefits from the construction

of complexes comparable to the Thames Barrier protecting the floodplain of greater London from high tides.

For instance, the erection of such a barrier could protect all of the low-lying neighborhoods about Jamaica

Bay from flooding. Given the rise of sea levels as a result of global warning such a solution will be

indispensable for the protection of all of the low lying communities facing this bay as well as New York and

the coastal communities of the greater region. Coupling such a barrier with high rises would also foster the

creation of ensembles of great architectural potential. All that is necessary is to address the future with the

courage of imagination. And here the objective of preserving natural, social and historic environments run

hand in hand.

One cannot underscore sufficiently how merely communal celebratory when not religious structures

constitute some of the chief foci of expression of architectural design, if not conscious civic life, across

history. This is evident in how such celebratory complexes in the Western World trace back to the basilica, the

great communal gathering space of the Ancients. And the equivalent of such buildings can be found in all of

the great cultural regions of the world. Indeed, it is precisely due to their joint value as civil as well as

religious structures for communities that the basilica -as well as all other equivalent building types- have

continued to serve as the focal point of communities even after they changed from civic to religious use, if not

from one religious group to another. This truth is all the more poignant when the site if not the structures of

Ancient Pagan temples were reconsecrated for Christian and or then Moslem religious use. Such changes

underscore the fundamental value of such structures as the crucial interface of cultural and civic continuity

across history and civilizations.

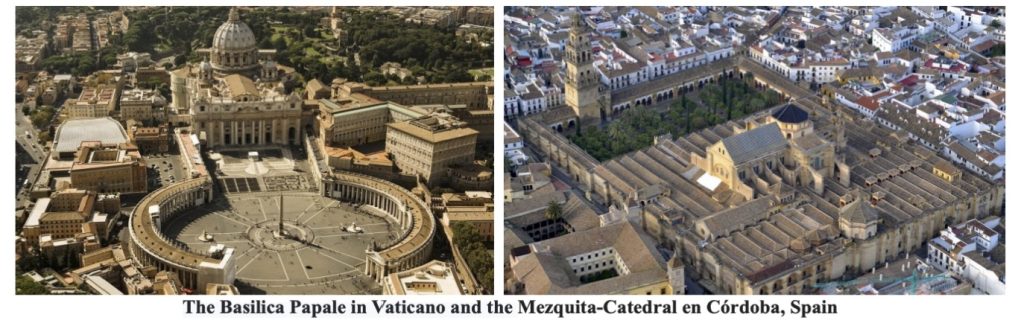

Indeed many if not all of the greatest architectural monuments of Humanity reflect if not embody

such a history. As such they embody a chronicle of history recorded in their stones. This is the case with

architectural sites of the magnitude of importance for all human civilization as the Basilica Papale di San

Pietro in Vaticano, or the Mezquita-Catedral de Nuestra Señora de la Asunción in Córdoba, Spain. Aside from

the profound religious significance of both of these architectural marvels, their value of vessels of socio

cultural continuity across history if not civilizations is perhaps of even greater transcendental importance.

Each site harbors the memory of the successive cultural centers which preceded their current use. As such

both embody the crucial value of their built presence as the vessels of cultural continuity which define the

identity their cities as historic socio-political entities. Most importantly such sites elucidate how the respect

for embracing such continuities are the foundation mirror of self consciousness of all civilizations.

And this truth is not only the same across all historical periods and civilizations of the past but is

crucial to enabling the very self consciousness of peoples to take form in current times. This condition is what

has enabled peoples to embrace the social condition of their habitats in the greater environments where they

live during all historical periods. Thus the architectural forms which the peoples of the world have devised to

create their habitats also explains the diversity of the forms invented to address otherwise seemingly

dissimilar needs of the peoples the world.

Although of much less spectacular character, the basic truth of this condition can be seen in the signal

importance of churches, temples or mosques as the focal architectural sites of all communities in New York

City. As such these ostensively religious buildings also serve as a barometer charting the well being in both

architectural and social terms of virtually all quarters in this city which they grace with their presence.

In New York City this condition is perhaps most evident in Brooklyn, a borough which still preserves

many of the historical continuities lost elsewhere. This despite also bearing the scars of urban renewal policies

devised to “improve” neighborhoods which were actually designed to destroy emergent foci of wealth and

power of minority communities. Here the Woodhull Hospital in Williamsburg provides a case in point.

Supposedly built to improve medical care for adjacent communities its construction entailed instead the

demolition of an entire neighborhood as well as the loss of a host of smaller neighborhood medical centers.

And that facility was merely one in a host of adjacent development sites which effectively destroyed a huge chunk of the historical fabric of central Brooklyn. Indeed the wonton destruction of all similar sites through

out New York threatens all of the greater city through the negation, if not erasure, of structures of civic

memory as vessels of consciousness.

Shockingly, here as elsewhere, once the victim of discourse on urban renewal as vehicle of social

betterment such sites are currently being destroyed left and right merely to suit the greed of so called

“developers” capable only of erasing the intricate web of social ties created over the course of social history.

And the evidence of such events in Brooklyn already provides an ample chronicle of the greater implications

perhaps already largely erased elsewhere in greater New York City.

Yet despite the ravishes of that period the architectural patrimony of many, if not most communities

in Brooklyn still survive. And this is due in no small part to the role of their churches as the center of their

communities. And quite an impressive assemblage they are.

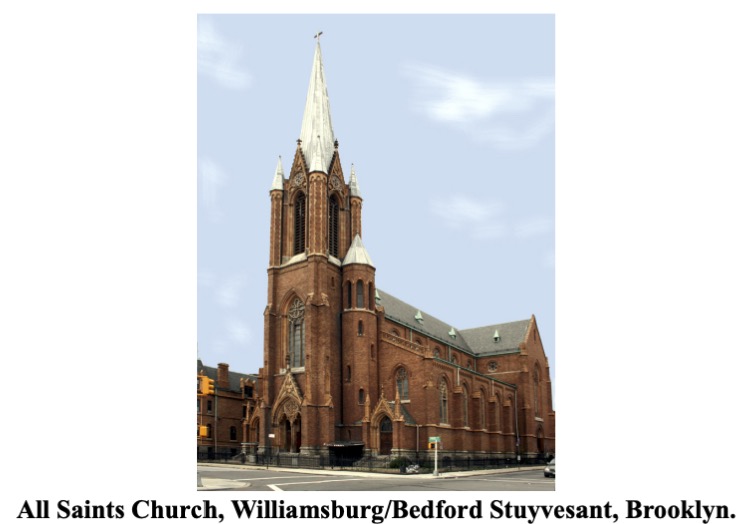

One cannot underscore sufficiently the wealth of memory of events, institutions and people associated

with or effectively centered on the religious buildings of any faith in the neighborhoods where they stand. A

few examples suffice to express these associations. Among these churches All Saints Church on Throop

Avenue in Brooklyn provides an excellent example of the throve of societal memories which all such edifices

harbor. For as long as it stands this church will continue commemorate the succession of German, Italian and

Hispanic communities which it served during its history.

Although the breweries and other industrial plants of this neighborhood in Williamsburg which

brought these people to settle here are long gone -like the bulk of the built fabric which housed them- only

this church alone remains to honor their collective memories. Indeed this church is perhaps the last remaining

vestige of a neighborhood erased purportedly to build public housing and hospitals for the greater good which

resulted instead in whole scale disenfranchisement and displacement.The best example of these policies finds

its poster child in the displacements caused by the destruction of a large segment of this neighborhood merely

to erect that elephant known as the Woodhull Hospital complex.

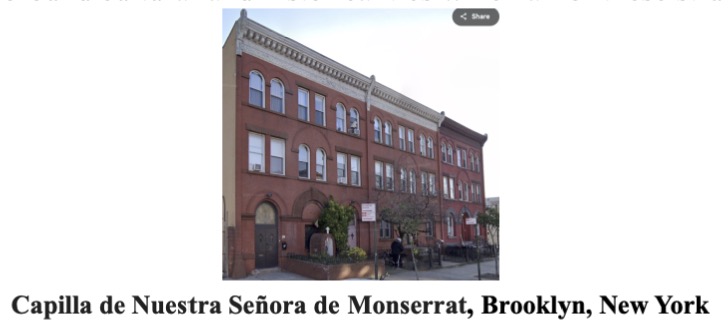

In contrast two of the many religious structures of Brooklyn exemplify the profound web of

connectivities which they embody. Together the Capilla de Monserrate and the Episcopal Church of the

Redeemer exemplify the profound cultural and historical ties which all of these structures embody.

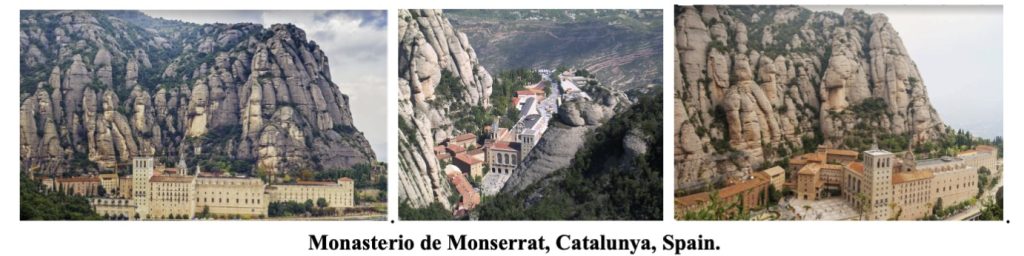

The Capilla de Nuestra Señora de Monserrat is a perfect example of the extended links of the

churches of Brooklyn beyond New York City never apparent in their physical presence. Established as a

mission of the Monasterio de Monserrat in Catalunya, Spain, its origins link this chapel with a missionary

establishment extending around the world. And as such this chapel has served as a place of congregation of a

community coming from throughout the Hispanic world since its inception.(2)

It is also important to note how -albeit situated in building originally erected as a converted row

house- this chapel linked its congregation to the greater world. As such it exemplifies the myriad of social and

church facilities emerged across history by reconsolidating building complexes in order to create a

community center. Indeed, this enables this church to meld with the civic fabric of the red brick and

brownstone buildings of the quarter where it lies. As such its architectural condition speaks to the intimate

links between religious centers and preexisting social fabric.

Together the Capilla de Nuestra Señora de Monserrate and All Saints Church highlight the important

role of the diverse church establishment of Brooklyn. Speaking from personal experience I can attest to the

immense importance of the relatively secondary churches in serving the special needs of their communities. I

will never forget the crucial formative role of the Capilla de Monserrate for my family and especially in my

life. The first excursion into the greater world came when I was thirteen and traveled to Europe with my

family on a trip organized by this church. Although ostensively focused on visiting the holy sites of Fatima,

Lourdes and Monserrate, that excursion also took us to Lisboa, Madrid, Barcelona, Paris and London, a

journey that opened the world before my eyes. I can only imagine the host of sites of sites that other small

scale religious community centers of all religions offer to their congregations. This speaks legion to the

importance of conserving and enhancing the presence of religious centers of comparable size for their

communities. Unfortunately the Catholic Church plans to close and demolish the Capilla de Monserrate, leaving only All Saints Church to serve their needs. This plan highlights only the sacrifice of the diverse communities of the Catholic Church as reduces the faith to that of its “nomenklatura”. Recent years have seen this church and it congregation threatened with destruction by those who would see this neighborhood reduced to one church, All Saints. Indicatively this chapel would be reduced to the site of new “housing”. Surely the existence of an extensive parking lot adjacent to this site rather than serve as an alternate site for this objective has heightened the ever voracious appetite of real estate developers.

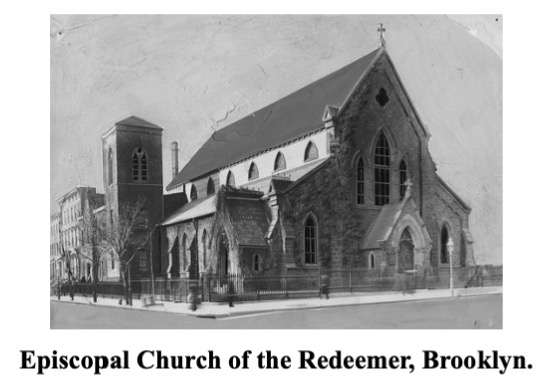

The fate of this quarter in Brooklyn highlights the destructive effects of so called urban renewal

projects on the genuine civic fabric of this borough. Whether public housing estates, schools or hospitals

ostensively built to “improve” the quality of life the effect on merely complement the negative effects of

contaminated industrial -sites such as the Pfizer Factory- immune to destruction. These blunders of the past

underscore the need to restrain unrestricted destruction of built fabric inherited from the past merely to

kowtow to a-critical acceptance to developmentalism. Another church illustrates the host of associations which the churches of Brooklyn harbor even further. And its destruction underscores all that has been is being and will be lost as well as underscoring the less than nothing that has taken their place. Such is the case with the Episcopal Church of the Redeemer that graced 4th Ave until recently. That church remained a key center of the community which it served from the date of the construction in 1866 as the second church on its site on the northwest corner of Fourth Avenue and Pacific Street, Brooklyn. Indeed, the construction of that church consolidated the presence of the community it was built to serve. Built to the design of the architect Patrick C. Keely, this humble edifice connected its community with all those others served by the 700 churches and 16 cathedrals also designed by this same architect across the North American continent over the course of his career. Born in Ireland, Keely arrived in the United States along with the thousands of his fellows forced to abandon their homeland due to the Great Potato Famine. Albeit built to serve community of the Episcopal Church- this facts illustrate how the construction of this edifice linked it with the great expansion of the Catholic Church -to which Keely belonged- across the United States. As such it demonstrates the power of architecture to serve as medium of self consciousness of peoples conscious of greater communities and thus the world.

Indeed after the memory and thus the presence of that sense of community remained after the death of

all of the generations which it served as both legacy and consciousness. However all of these memorable

associations were erased with the destruction of the Episcopal Church of the Redeemer only a few months

ago. All of this merely to erect yet another monument to what must be recognized as the great sin of our age,

the ever present greed of Real Estate speculators. Thus the destruction of the vessel of memories that was

Episcopal Church of the Redeemer a few years ago gives its absence even greater historical importance. As

such the site of this church is indeed now a worthy -if sad- monument to this scourge.(3)

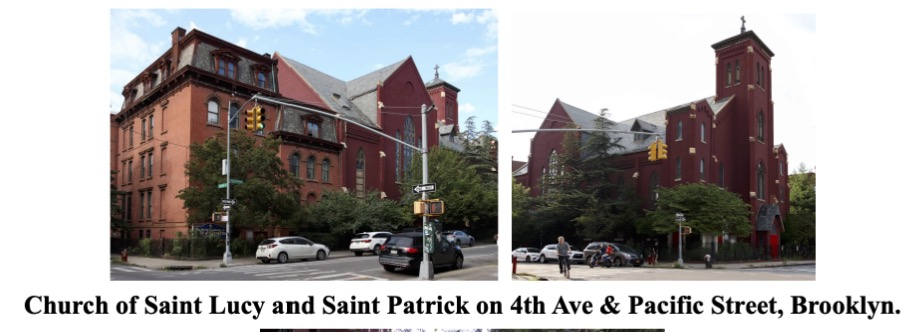

However, the best -and most tragic- example of this scourge can be found in what could and should

have been done to avert such losses is the Church of Saint Lucy and Saint Patrick on Willoughby Avenue in

Brooklyn. It was demolished merely to erect new luxury housing on its site. If that were not tragic enough, all

of this could have been averted with a little imagination in how to adapt building codes to make the best of

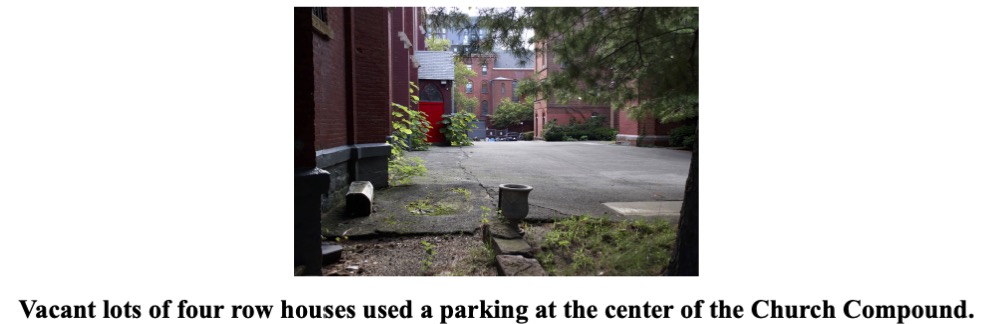

other possibilities. This church compound consisted of a church, a rectory and a school separated by a parking

lot equivalent to a double pair of lots for row houses back to back. That condition would have been possible to combine the maximum Air Rights of this compound as a whole to build a taller structure on the site of this

parking lot. The simple measure of granting permission to transcend the maximum building heights for that

district as a whole is all that would have been necessary. Indeed, such a structure could also have included

underground parking on this portion of the property to fit the needs of any new building. And to this one could

add the continued basic value of the the church building itself as a vessel of social reunions adaptable to new

ends. Such simple measures would have saved an architectural ensemble of historical value while also

providing the space for new housing.

Such a strategy would have preserved the compendium of buildings already on this old church

property, a site of historic importance for both this quarter and Brooklyn as a whole. All of the structures on

this site could have been converted to other uses. Indeed in accordance with the origin of all church

compounds in the basilica as an open tipologia edilizia it would have been very easy indeed to reinvent this

compound to serve as the ongoing community center under whatever new management.

Perhaps there is no better example of the threat to the erasure of the memories which the religious

structures of Brooklyn embody than what how the West Park Presbyterian Church on West 86th Street and

Amsterdam Ave in Manhattan is being saved. There the twelve and thirteen story apartment building which

flank this church on either side exemplify the appetite of Real Estate interests which would destroy this

architectural gem merely to erect a new building of equal if not greater size as its neighbors.

Yet this church site also exemplifies the rebirth of this church through its effective return to serve as a

basilica. Here the fundamental role of all such religious structures as a community center found expression in

how it has been refitted to host a multitude of cultural and other activities. As such it has returned to the

fundamental role of all basilicas as centers of community protection and development.

The problem is that currently the loss of communal attendance of these religious structures has greatly

hampered the ability of their communities to maintain them. This has provided ever rapacious would be

“developers” with a double excuse for appropriating this architectural legacy in order to replace it with only

rarely at best mediocre, yet pompous, “housing” as “luxury” commodities. Indeed, even a summary review

reveals that what is worse such projects are not even conceived to address the lack of housing so evident

today with which they justify their rampage of destruction of civic fabric. Instead their true primary purpose is

merely to provide tax breaks for investors. Thus the traditional communal centers of Brooklyn are being

replaced by husks destined to remain empty despite the acute need for housing in all quarters of New York

City. Ironically however, these piles do indeed now embody instead the malignant presence of real estate

speculation as as jackal like harpies of mis“development”, the true cause of the housing crisis to begin with. One cannot sufficiently underscore how this tragic turn of events constitutes a clear symptom of an

even greater epidemic of destruction entailing all vestiges of the societal memories and knowledges which

those buildings embody. Unfortunately, today the cities of the world are threatened by a discourse which

reduces civic form to ever fewer norms of globalizing urbanization. In this way the wealth of socio cultural

continuities embodied in any one building are erased to erect structures better described in terms of their

“market value” as embodiment of all important “Real Estate” über alles. Thus the possibilities present in

many if not all buildings whether singularly or as expressions of greater architectural languages are dismissed

in favor of inculcating mindsets capable of perceiving only reduced sets of vacuous real estate norms. In this

way the adaptability of building, and especially communal religious structures, is reduced to “containers” deemed useless as they do not fit the image vulgarly associated with “housing” or structure whose

architectural presence can be sufficiently erased to be easily in order to convert them into “condominiums”.

All of this can be avoided through the adoption of two measures capable of granting owners of

religious and other buildings of notable historic value the ability to continue serving as communal centers

despite the loss of their traditional parishioners or communities. And these measures are as simple as

empowering the scope of existing legislation: the sale and the transfer of “Air Rights” (a.k.a.“Unused

Development Rights”). Yet at present “Air Rights” have only limited transferability. Thus as such at best this

measure can only serve as a means for the current owners to cancel immediate debts at the cost of the

demolition of the building and all associated memories. Equally problematic is the limited transferability of

the sale of these air rights for use in adjacent sites and not even in their immediate districts. Indeed, even if the

transfer of “Air Rights” to other sites in their immediate district were possible this would generate even more

pressure on the greater historic zones where these buildings stand. In short, all too often these limitations on

the sale of air and transfer of “Air Rights” serves only to generate even more pressure on the inevitability of

the eventual demolition of the religious and other communal structures of architectural if not explicitly

historical merit.

However, such tragedies can be avoided while truly providing more new housing and other necessary

social facilities for all communal and other needs. This can be achieved through fostering four measures

which combine both the preservation of historic sites as vessels for communal life new as well as old with

measures capable of addressing the threat posed by climate change to the greater environment. This calls for

empowering the recurrent sale and transfer of “Air Rights” to underdeveloped coastal edges of the city

threatened by sea level rise. This entails recognizing the complementary condition of preserving historic sites

while enhancing environmental preservation. Thus in summary:

- Enable the sale of the “Air Rights” of buildings of historic when not architectural merit on a recurrent

basis. Thus, by enabling the sale of “Air Rights” for such structures every five or other years in

accord -if not against- the changing cycles of Real Estate speculation, such buildings would be

provided with a means to finance repairs or restoration and maintenance into the future. This would

also foster restoration work of the many structures in general and thus strengthen if not generate an

important source of employment within all communities.

Such a simple reform of the zoning laws will be a great help in fostering the both the preservation

of historic structures and the communities which they served. Indeed enabling historic sites to sell

their “Air Rights” in response/defense against real estate building cycles will provide them with a

recurrent source of income incentivizing the preservation of historic and communal resources against

demolition well into the future. - Direct the transfer of air rights from their local districts to sites located adjacent at the coastal edges of

Brooklyn and greater New York City. This will not only protect both such historic buildings as well as

their greater historic zones while increasing their market value. Indeed the transfer of “Air Rights” of

such buildings outside their immediate zones to other sections of New York would greatly lessen the

pressure on all historic districts. In addition, duly regulated, such a measure will foster greater control

over the design of new communities in currently empty, if not derelict, zones of greater Brooklyn

when not New York City or the United States as a whole. Indeed, these development site would create

a sea wall designed to protect low lying neighborhoods inland.

Such a measure for example would enable the salvation of all historic sites comparable to the building

on 227 Duffield Street (aka Abolitionist Place) in Downtown Brooklyn which currently remain threatened.

Once forming part of the underground railway during the struggle against slavery that site exemplifies the

essential role of all building -and especially churches- as social and historical condensers. Currently all other

such buildings are threatened with demolitions to satisfy the avarice of the harpies of Real Estate simply to

erect yet another 32 story glass box monstrosity on its site if not to carve out another of those empty lots

which pass for “plazas”. Indeed the destruction of comparable historic sites merely to feed the mindless greed of real estate speculation serves as a thought provoking expression of the ever present roots of slavery

still in the soul less commercialization of life in the world today.

- Embrace the historic role of religious structures by returning to their origins in the basilica as a

tipologia edilizia to underscore new roles as centers of other explicitly contemporary communal

purpose. - Enable new construction where open space permits the concentrating of “Air Rights” accumulated

from historic districts elsewhere. This will further foster the creative reinvention of the greater

properties of religious and other communal sites where possible by enabling the use of their open

areas for new buildings accumulating the “Air Rights” of the entire property on a portion thereof.

This is an especially important alternative in the case of compounds possessing open grounds for

parking. Such cases would permit buildings channeling part or all of the buildable heights of the

collective lot to one higher structure. - Foster the creative adaptation of exiting buildings by designing additions on top of their historic

fabric. This would take a cue from early skyscrapers where the design ground level facilities

explicitly reference ancient basilicas.

Here the Williamsburg Savings Bank Building near the juncture of Flatbush and Atlantic Avenues in

Brooklyn is a perfect model for what could be achieved by following the best of millennial design traditions.

The tallest structure in Brooklyn when it was completed, the design of this building combined a bank modeled

on ancient basilicas on ground level with multiple commercial floors above. Surmounting all in turn the bell

tower -which also references similar structures in church building- announced the ensemble as a whole. And

long since abandoned for either use, this building has largely been converted to residential condominiums. As

such it underscores how existing church buildings can also be converted to other uses by adding new floors

above. Why not?

The location of this building next to the Central United Methodist Church on Hanson Place -a church

building of exceptional design which is also threatened with demolition merely to feed the avarice of the

jackals of Real Estate- provides a poignant focus of reflection on the creative means to avert the threat at

hand. One can imagine what could be achieved in the worse case scenario with a creative design mimicking

the design strategy of the Williamsburg Savings Bank Building next door by erected a new structure above the

existing church without demolishing the building below. Such would make a wonderful challenge for

architectural design competitions worthy of the name.

Indeed the ongoing threat to the Central Place United Methodist Church on Hanson Place and St.

Felix Place next the Williamsburg Savings Bank Building and Atlantic Terminal exemplifies the need to

create other vehicles with which to empower the communities which they served as soon as possible.

Together measures such as those suggested here will strengthen the viability of the preservation of

communities as well as historic sites throughout Brooklyn as well as New York and the greater surrounding region as forerunner for the entire world. Only this can protect New York from the sweeping threats to some

of the most key historic sites. And the opportunity to do so will also enable addressing greater environmental

threats on the horizon.

In these times in which Real Estate seeks to achieve new depths of imperial ambition by usurping the

vestments of Holy Lands merely to plop excremental constructs sold as new “Rivieras” it is more important

than ever to empower the vessels of genuine communal memory and environmental security. Empowering the

Air Rights of historic and communal sites through perpetual renewability and expanded transferability

protects not only structures of historical and communal presence but also the larger environments of those

who they serve as greater societies.

Once can foresee that the expansion of Air Rights will create a powerful economic resource for both

the communities which the buildings so empowered serve as well as the greater society at large. Indeed the

renewability and increased reach of transferability of Air Rights proposed here will surely create a whole new

banking system enriching as it empowers the communities which these buildings serve. And one cannot

diminish the importance of directing the transfer of such Air Rights to projects sites addressing the increasing

need of protecting settlements from the environmental threats of climate change. This amounts to honoring

both the vessels of communal memory as well as engaging in the proactive preservation of the environments

of future generations.

- https://gothamist.com/news/archdiocese-of-ny-plans-to-sell-124-year-old-east-harlem-church-to-property-developer

- “Our Lady of Monserrate Church”, http:churchangel.com

- Opening in 1866, the Episcopal Church of the Redeemer was built on the northwest corner of Fourth Avenue and Pacific Street as per the Gothic-inspired design of the architect Patrick C. Keely. As such it was one of the 700 churches and 16 cathedrals designed by this architect. Like so many other historic buildings, this church embodies many crossed histories. Although of Episcopal faith, it like the other churches designed by this architect reflect the upsurge in catholicism following the mass migration of Irish people to the United States as a consequence of the great famine. Following years of declining membership, the congregation began worshiping at St. Luke & St. Matthew Church (Clinton Hill) in Brooklyn. The building was closed in the Spring of 2012 with plans to redevelop the site. And it was then demolished simply to build yet more luxury condominiums. While peddled under the heading of the need to address the lack of “affordable housing” this project, like so many -most- others, came about merely as a means to acquire a tax break for developers who will then sell them as luxury apartments for the nouveau riche. Like most other similar developments most of its apartments stand empty to this day.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hanson Place Central United Methodist Church, The Hanson Place Central United Methodist Church is a Methodist cathedral in the Fort Greene neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York City, located on the northwest corner of Hanson Place and St. Felix Street, adjacent to the Williamsburg Savings Bank. The church is the third Methodist church on the site.[1] The present structure was built in 1929–1931, and its architectural style has been called “Gothic restyled in modern dress, an exercise in massing brick and tan terra cotta that might be called cubistic Art Moderne.”